RENAMING THE Concours Artistique Du Quebec

Readers of this text, forty years after the event, may know, or recall, little of the political atmosphere in Quebec in 1971, when the annual Concours Artistique du Québec was renamed Exposition des Créateurs du Québec. It was an atmosphere still smouldering from a decade of explosive violence that I thought it helpful to describe before the rather brief catalogue text.

The word “concours” can refer simply to a “show” but it can also imply a competition, whereas “Exposition” is unambiguous. Such a change may be seen by some as trivial, but nothing that changed in Quebec in those days was trivial, as an account of the previous decade will show.

In spite of the poignant 1948 appeal for change by the self-styled “Automatiste” group, in their manifesto, Refus global (addressed as much to the social sphere and the Catholic Church as to the situation of the arts in Quebec), little was to change of the collusion between the Church and the ultra conservative Union Nationale, a political party which was to last for another 12 years until the death of its tyrannical leader Maurice DuPlessis ended his 24 years of power and finally made way for the Provincial Liberal Party under Jean Lesage.

The new regime soon began a series of changes that secularized education, created a welfare state, nationalized Quebec Hydro and raised the life of the majority of Quebecers above the poverty line. Such measures have been named “The Quiet Revolution” to distinguish them from an attempted violent revolution that was anything but quiet, especially after Lesage was re-elected in October 1962—for in March of that year Algeria had gained independence from France after a long and bloody struggle led by the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), and almost as if taking a cue from the Algerians the non-violent Lesage chose to run under the slogan “Now or Never: Masters in Our Own House.” Not only that, but everyone in Quebec knew that the following year, 1963, would mark the two-hundredth anniversary of the ceding of Quebec to the British—an anniversary bound to invite political ferment among Quebecers still smarting from Anglophone dominance in French Canada. All the same, Lesage could scarcely have imagined that his slogan would invite the formation of groups far more radical than his Liberal Party—groups based seemingly on the violence with which the FLN had won freedom for Algeria, the best known of which came to be the “Quebec Liberation Army” and the infamous FLQ (Front de Libération du Québec). In short, by the end of 1963 dynamite bombs had exploded in the postal boxes of Montreal’s affluent Westmount district as well as at the Stock Exchange, the RCMP recruitment Centre and various military sites; Wolfe’s statue on the Plains of Abraham had been (inevitably) destroyed and bank robberies to sustain the coffers of the insurgents were soon commonplace—even though there were arrests due to the betrayal of some insurgents by one of their own in response to published rewards of $60,000.00 (the equivalent of about a half million dollars today).

This situation was perpetuated through the rest of the 1960s, during which there was not a month when a bomb did not go off with injuries or deaths, and though there was a let-up in 1967, the year of the Montreal World’s Fair (popularly known as “Expo 67”) (1) bombings increased in 1968, perhaps inspired by a sense of community with the student uprisings of that year and the Marxist-Anarchist violence associated with them in both Europe and North America—violence which, among much else, incited both the destruction of the computers at Sir George Williams University in 1969 and the high-jacking of a Boeing 727. Then, in 1970, the FLQ took hostage the British Trade Commissioner and the Minister of Labour of Quebec, Pierre Laporte, who was found days later dead in the trunk of a car, “executed,” said the FLQ.

The “execution” of Pierre Laporte, however, became a turning point: the Premier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa, who had recently followed Lesage, and the Mayor of Montreal asked the Federal Government for help and Prime Minister Trudeau declared the “War Measures Act” which, with huge popular support, brought the army onto the streets of Montreal and allowed the police to make 400 arbitrary arrests—without warrants and with the suspension of habeas corpus— actions which uncovered whole lists of members of the revolutionary cells.

It was during this “October Crisis,” as it came to be called, that Quebec artists, some sympathetic, if not active, with the insurgents, adopted their own idea of a “Front” and staged their own “rebellion” against the Minister of Cultural Affairs, gaining for themselves a meeting in the Bibliothèque Nationale on November 28th whilst, as a result of the “War Measures Act” and the assassination by the Canadian Secret Service of Mario Blanchard, a leader of the FLQ who had fled to Paris, the remaining leaders of the FLQ took flight and the bombs grew less—and may be said to have stopped completely in 1972.

The artists (the word here includes painters, sculptors, crafts people and printmakers) had a list of complaints which had long been simmering in the press regarding greater funding for visual arts and a variety of new long term projects. But what concerns us here was their resentment towards the structure of the annual Concours (see above) which they demanded to see radically changed before they would allow it to go ahead in the coming year. They cited its arbitrary regulations and its perceived injustices and demanded participation in the formulation of new rules and regulations. These included the end of its competitive basis (that left out-of-pocket those not winning a prize), an end to the restriction of the size of submitted works to 20 square feet per canvas, with parallel restrictions for sculpture, and an end to the tardy announcement of dates that came too late for many outside Montreal to participate.

As one meeting followed another, the art critic of La Presse, Normand Thériault, like many others, attacked the minister on all these counts, pointing out at the same time that visual art in the 1970s would no longer be a matter of paintings and sculptures but also of “happenings,” conceptual art and “installations.” He also referred to the disgraceful level of financial aid for visual arts compared with the budget of the Ministry itself and its art bureaucracy.

It was not until the following April that that an agreement was reached which satisfied some of these demands: the name “Concours” with its competitive overtone was to go, even though five works might still be bought by each of the Musée d’art contemporain in Montreal and the Musée du Québec in Quebec City, at a fixed price of $1,500.00—a policy to which any artist who wished to submit works would be obliged to sign an agreement. As for those artists whose works were not selected by the two museums, they would get $500.00 to cover their expenses and for that would have to allow their works to be distributed by lottery among cultural centres across the province to which the show would be scheduled to travel for the “diffusion of culture.” In short, and if this were to be followed through, the former “competition” had now become a lottery!

However confused and confusing this may seem, from then onwards the event was to be re-named “Exposition des Créateurs du Québec” and would show for three months in Montreal before going on tour. Furthermore, it would no longer take place at the Musée d’art contemporain but at the Québec pavilion at Terre des Hommes (2) on the former site of “Expo 67.” Fifty artists would be selected, half from the cultural region of Montreal and half from the rest of the province and their selection would be by a single “judge-critic” from outside Québec, appointed by agreement of the professional artist groups. Size restrictions, however, would remain unchanged, to allow for transportation and the handling of the works as they travelled. The “judge-critic,” whose selections would be final, would travel to designated centres across the province where works would be presented anonymously and, if necessary, with names and signatures covered by tape.

Guy Monpetit, President of the Society of Professional Artists, who claimed that his show of the previous year at The Musée du Québec had cost him $4,000.00 to install and who played a leading role in the contretemps, now announced that the artists had a “firm ally” in the Minister and that the change of venue from the Musée d’ art contemporain in downtown Montreal to the Terre des Hommes was generally agreed to be a wise strategy, to avoid vandalism or incidents in the Musée or the Place des Arts where it is located, vandalism not only by artists still not satisfied but also by a public indignant in regard to political works that might get into the show or even by those who simply objected to “modern” art. However, once the process was under weigh, the minister added unpredicted measures of his own regarding the actual event—which was minimally advertised, had a very private opening and remained unannounced on the exterior of the Quebec pavilion which was covered by a display of flags bearing the fleurs de lys instead—all of which was commensurate with the fact that, whilst granting huge support to the more glamorous theatre and opera companies, neither of Montreal’s two major art museums had received government funding during the whole of 1970! One result was that scarcely a catalogue was sold, even at the price of $2.00.

Nevertheless, after a later reopening of negotiations, it may be said that the minister promised to reinstall the 1.5% tariff to provide art for new public buildings, provide a tax relief for artists and create a Quebec “Art Bank” similar to that to be realized by the Federal Government the following year (for which, I should add, I was to be one of four jurors chosen, by the usual federal method, from across the country).

Needless to say, there had been a lengthy and acrimonious discussion about the composition of the 1971 jury before it was settled as outlined above, at least for 1971, since the art societies all wanted to be represented, although it was argued that the result would be “dirigisme” if artists were to judge artists. There is on record, for instance, a fragment of the discussion between three of the participants which went as follows: (person A, optimistically): “We would like to suggest Mr. X” (a well known collector).... (person B, scathingly): “We have never heard of him”.... (person C, drily): “He’s in the Molinari clan.” [Readers may know that Guido Molinari, married to Fernande Saint-Martin one of Canada’s most distinguished art world intellectuals, was a powerful voice among the few Quebec painters of the time acknowledged Canada-wide]. In the end, however, it was indeed decided to seek a single juror from outside Québec, and the outcome of that was that sometime in late April I received a phone call from Guido to ask if I would take the job—which I did, knowing very little of what had transpired except that there had been a row and the three Artist’s Societies had agreed on my name.

Surveying all this for the Gazette, Normand Thériault, on May 15th, wrote an article headed by a quote from Voltaire, surely with tongue in cheek, Tout irait donc pour le mieux (“So all was for the best”), implying Voltaire’s irony but leaving out Voltaire’s “in the best of all possible worlds,” for though, at the same time announcing the government’s provision of $100,000 to cover the deficits of un-named museums and “talk” of new buildings, he thought it appropriate to add that “nothing concrete” had so far been announced!

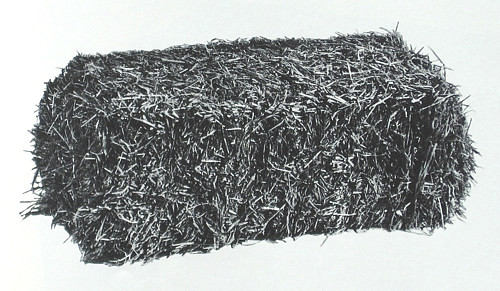

Thus it was that I travelled throughout Quebec by car and plane as a guest of the Quebec Minister of Cultural Affairs, learning through conversations with different Quebecers as I went, on an expedition that ended at the Terre des Hommes just after the delivery by L’association des sculpteurs du Québec, or so I believed, of bales of hay or “balles” (or “boites) de foin” (3) which, in the style of a militia, they called “Operation fourrage!” In fact, the Sculptors’ Association, while it had been vociferous throughout the entire controversy, had finally announced that its members would not participate – as if hoping that they would thus be able to commandeer the entire show in 1972, but in fact because they had secretly planned the “Operation” rented a truck containing 40 bales of hay: one “sculpture” from each of forty or, as some said, fifty members, counting student participation!

No doubt this was aimed to cause an embarrassing furor, and officials of the Ministry were still in shock, but having already shown artworks at the Art Gallery of Ontario more challenging than bales of hay (4), I reasoned that it would be perfectly commensurate with my role to select at least one bale and have the artists collect the rest, and in the event I chose one that had arrived as if from the studio of Serge Cornoyer who, some said, had been an instigator of the plot.

There were, inevitably, other politically orientated works, both earnest and satirical, and I chose one of each which can be seen among the illustrations below. I also gave a nod to the naive art, found sometimes at the more remote assembly points, by choosing one that I found appealing. However, in the brief preface allowed me in the catalogue, I did not think it appropriate to comment negatively on what I had found but thought such a comment would be more appropriate in interviews with the press—where I announced my disappointment at the scene in Quebec and attempted to lay it at the doors of both the Ministry and the conservatism of the artists themselves.

CATALOGUE PREFACE

Originally, this exhibition was to have been an attempt to push a little nearer the realization of a cherished dream: that of reconciling art and people. The works, that is to say, have come not only from a city of avant-garde polemics, like Montreal, but from eight centres throughout the Province of Quebec, and were to have been returned there, both to be seen on exhibition and to be distributed by lottery among the various communities of origin. This plan has now been modified, but its initial existence will partly explain the range of styles and the different levels of sophistication to be seen.

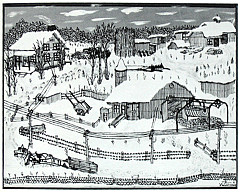

To be an artist in the cultural centres of the West today is to take part in a debate about the nature of art, not so much through words as by the works that one makes. The alternatives in Quebec Province seem to be twofold. When cut off from such debate the individual responds instead to his immediate environment—to climate, physical surroundings or the impact of mass media; or, lacking Beaux Arts skills, he is driven to create by the pressure of inner fantasies. Thus, some works in the exhibition do not reveal an obvious international ambition. Instead, we find the terrifying image of a phoenix failing to rise from the muddy wastelands of Rouyn, an elegy on the death of a pop singer, or a naive and lyrical fantasy on winter in a farming community.

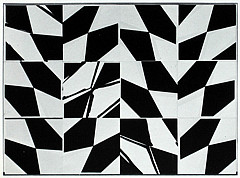

In contrast, among artists engaged with the international debate (mostly from Montreal) the range of expression extends widely—from a characteristic loyalty to European non-figurative painting or kinetics, to an increased receptivity of American lyrical abstraction, polemical gesture, or the art of brute materials.

No single aesthetic can embrace all of these. Yet without doubt, each category has established its claim to attention; and behind each lays the aspiration to enhance life—explicit in an arrangement of sumptuous colour or subtle light but present too in the cry of anguish or the defiant or comic gesture.

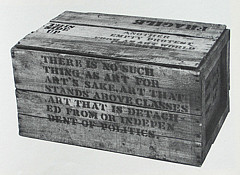

One item, the bale of hay, or straw, plays a double role: it is both the index of a contention between artists and government, and something which exists for its own sake. Visitors may be shocked to find a bale of straw in an art exhibition—but hopefully from this very fact they will retain, more vividly than from any painting, the image of its yellow bristles, its shape compacted ruthlessly by steel wire, and its air of invitation.

In spite of the vicissitudes through which the regulations of the exhibition have passed and the original limitations in size imposed on each work, we find in the large number of artists represented a clear indication of the breadth, the vitality and particularly the growth points of the Province's plastic art today.

DENNIS YOUNG

Curator of Contemporary Art, Art Gallery of Ontario

Red Herring, (1971)